Before asking his patients about their medical needs, Thomas D. Huggett, MD’85, MPH, likes to begin his appointments with another topic: their goals.

Huggett, a family medicine physician who has spent three decades working with marginalized and unhoused people on Chicago’s West Side, knows that those goals might differ from the typical concerns a doctor might hear about weight loss or managing cholesterol.

“Some people want to find steady employment or stable housing, while others are looking to not use street drugs or reconnect with their family,” Huggett said.

As medical director of mobile health at Lawndale Christian Health Center, Huggett and his team offer primary care services at 20 shelters, including 12 traditional sites and eight dedicated to migrants.

This story appeared in Medicine on the Midway magazine. Read the Fall 2024 issue here.

He sees conditions as varied as diabetes, hypertension, wounds and skin infections, mental and behavioral issues, and substance use disorder — and he knows the housing insecurity issues that may exacerbate them can happen for many reasons, sometimes without warning.

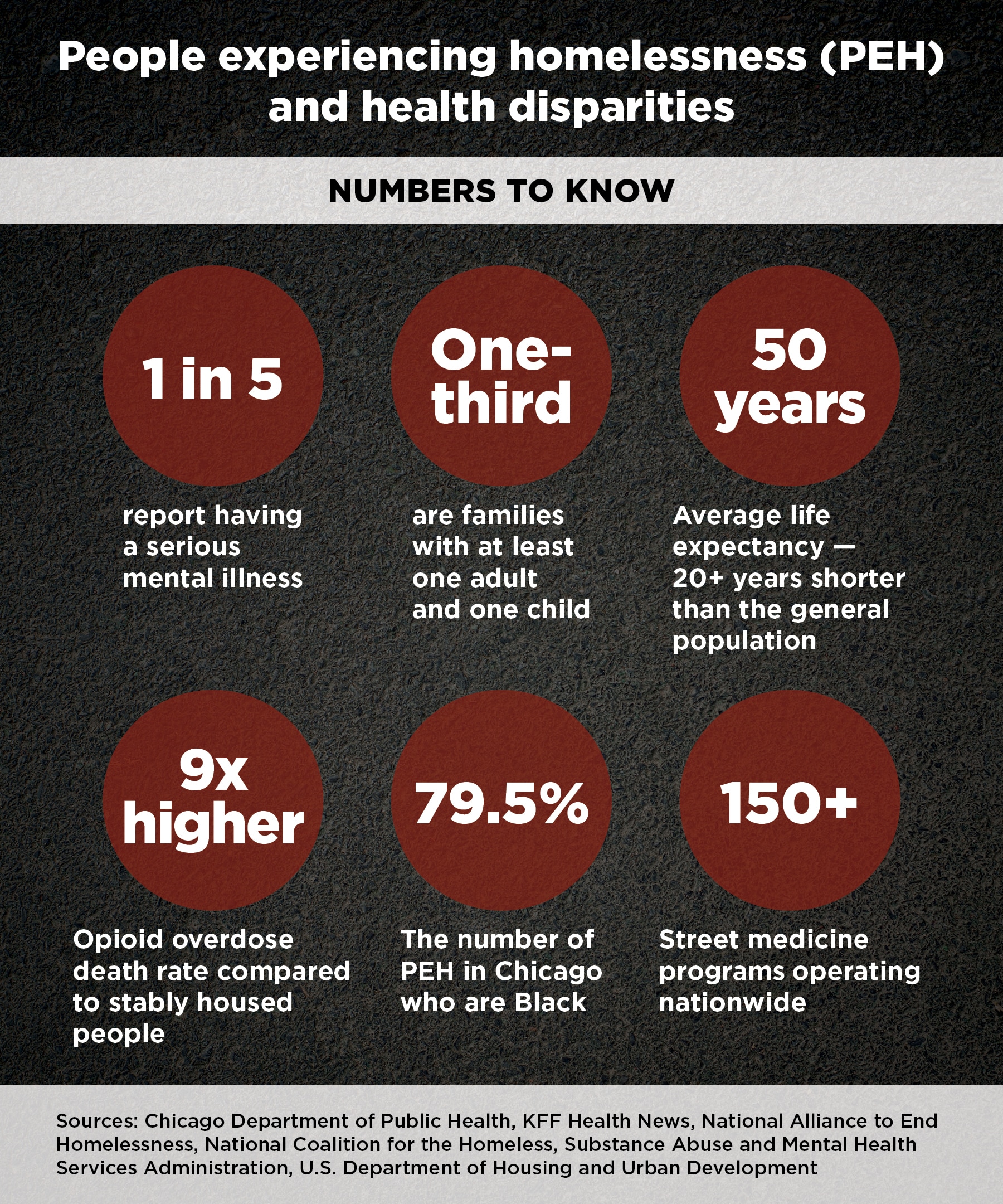

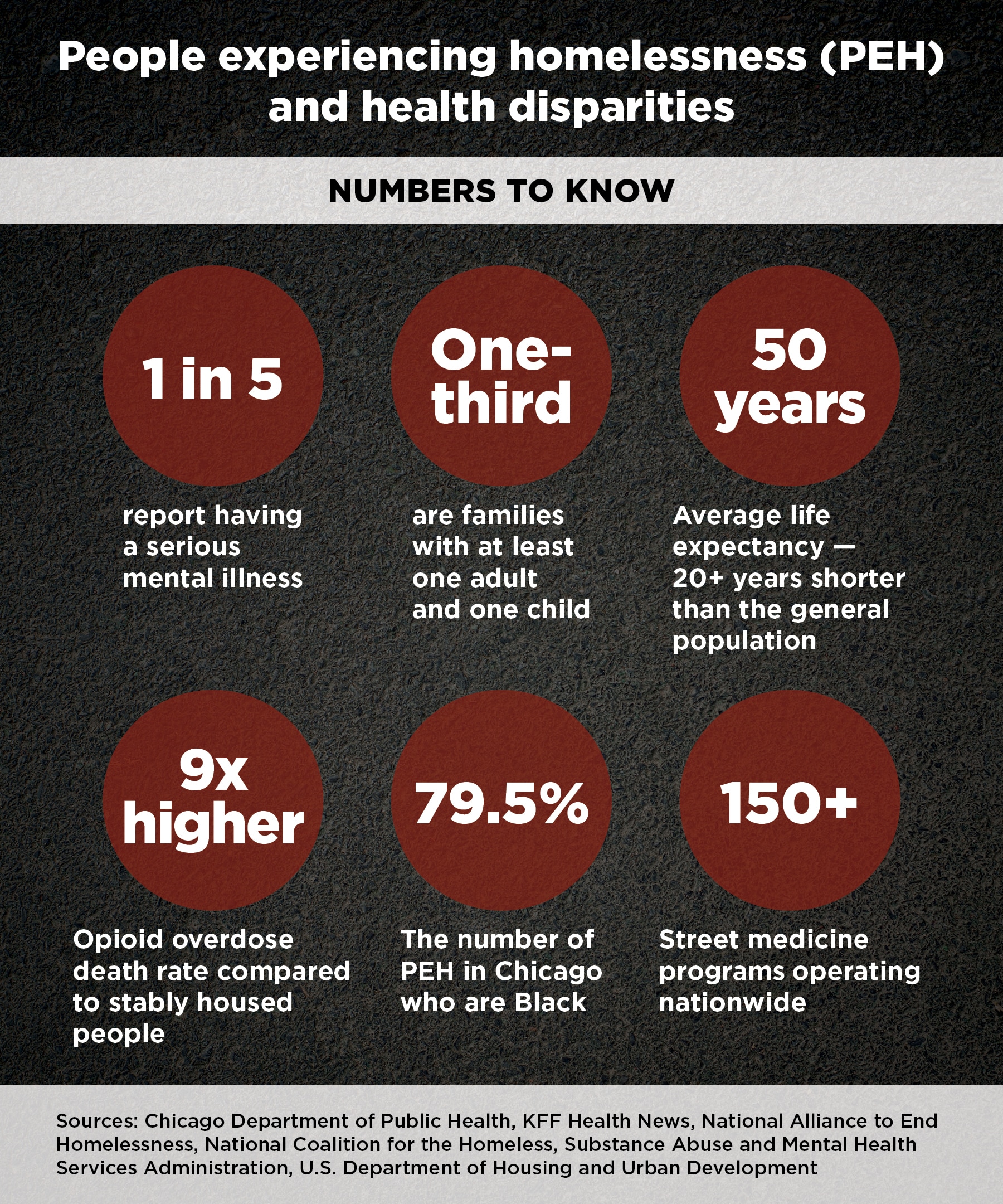

For Huggett and other clinicians working in shelters and among an estimated 150 “street medicine” programs nationwide, the workloads are rising.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development saw the number of people experiencing homelessness (PEH) rise 12% from 2022 to 2023. Last year, it recorded the highest point-in-time count of PEH — more than 650,000 on a single night in January — since reporting began in 2007.

Similarly, Chicago officials cited a PEH count of 18,836 on January 25 for the city’s annual point-in- time recording, a threefold increase from one year earlier. That total includes migrant arrivals bussed or flown in from the U.S.-Mexico border.

Huggett’s mission, motivated by his faith, remains steady amid challenges and change.

“Our intent is to provide a very low barrier to care, to build rapport and relationships so that over time we may have the opportunity to deliver care to our patients, and perhaps connect them with housing and traditional outpatient services,” he said.

Expanded care and approach

Chicago’s influx of migrant families has prompted Icy Cade-Bell, MD, Medical Director of the Comer Children’s Hospital Mobile Medical Unit and an Associate Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Chicago, to expand her team’s capabilities and the age range that they serve.

The Comer Mobile Unit has been treating children ages 3 to 19 in medically-underserved parts of the city’s West and South Sides since 2002, and it typically partners with area schools to provide sports physicals, health screenings, vaccinations, lab tests and more.

But about a year ago, the clinic on wheels began pulling up to area police stations, where new arrivals were housed on a short-term basis, and later at shelters. The unit also started seeing patients as young as infants and as old as 24.

Cade-Bell and her team also adjusted their approach to care. With no medical records to review, they spent more time uncovering the health needs of their patients. They worked through a Spanish-speaking interpreter, either in person or over the phone, and focused on providing trauma- informed care and connecting individuals with additional services.

“Working with new arrivals has been a learning experience for us, because they have these layers of concerns that go above what we typically encounter with our public-school students,” Cade-Bell said. “It requires a set of cultural competencies that takes into account the harrowing experiences these individuals may have faced.”

Cade-Bell’s experience underscores the complexities of working with marginalized populations, where medical care may require more than writing a prescription or devising a treatment plan.

These patients often have competing needs and priorities, such as court dates and Social Security appointments, and they can face transportation obstacles to attending appointments or obtaining medication.

Beyond logistical challenges, some individuals may harbor a distrust of the medical profession due to prior traumatic or discriminatory experiences, further delaying or complicating vital care.

“Many people who are living in the streets have been burned by the system,” said Jonathan Sherin, PhD’97, MD’98, who served as director of the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health from 2016 to 2022. “By that, I mean taken to the hospital, often against their will, and medicated, often against their will.

“This puts clinicians in league with a system that has been very traumatizing.”

Leading with heart

In his former role with the country’s largest public mental health department — which serves an area of 10 million people, about the same population as Georgia — Sherin focused on relentless engagement and treating patients with what he calls a “heart-forward” approach.

Sherin remains proud of developing the Homeless Outreach and Mobile Engagement (HOME) program that focuses on the most severely ill individuals, those with a chronic psychiatric disorder, schizophrenia, and likely comorbid health problems and addictions.

The model, deployed throughout Los Angeles, uses outreach teams to approach individuals in need of medical care by bringing them comfort items like food, toothbrushes and socks. Over time, as trust develops, teams begin to talk about medication and other treatments. The team involves the patient — as much as their illness allows — as a partner in the decision making about their care.

“It’s about reaching individuals in the most humanitarian way and restricting their civil liberties as little as possible,” Sherin said.

Peer engagement using former PEH who have overcome addiction or mental illness can also help create a bridge between underserved communities and healthcare providers, said Jeffrey Eisen, MD’09, acting deputy president and chief medical officer for the behavioral health division of MultiCare Health System, the largest provider of behavioral health programs and services in Washington state.

Eisen’s division runs a program called Projects for Assistance in Transition from Homelessness (PATH) that employs a team of peers and case managers to help PEH transition into shelters or other housing. The team connects with individuals in homeless camps, meal sites and other locations to support their search for steady housing and to enable their access to medical care and social services.

The program’s success comes from bringing people who lived the experience into the equation, said Eisen, who, as a student at the Pritzker School of Medicine, volunteered at the University of Chicago Maria Shelter Health Clinic, a shelter in Englewood providing healthcare to women and children.

“Peers understand the mental health concerns these individuals have and how difficult it can be to maintain housing or employment when you are not feeling well,” Eisen said. “They also have learned ways of navigating health systems that they can teach to others to help them more successfully connect with care.”

Reflection of community

A deep focus on health inequities and disparities is critical to tackling the diverse and complex needs of PEH and other marginalized groups, said Pilar Ortega, MD’06, vice president of diversity, equity and inclusion for the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and a Clinical Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine and Medical Education at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Racially and ethnically minoritized populations are disproportionately affected by housing insecurity, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Black people make up 13% of the U.S. population but comprise 37% of PEH. Asian Americans experienced the greatest percentage increase among PEH, increasing 40% from 2022 to 2023. Individuals who identify as Hispanic or Latino had the largest numerical increase, rising 38% during that period.

Medical education has the potential to impact PEH and street medicine efforts by encouraging students from underrepresented communities to enter the profession.

The reason? “They are often the ones who are most motivated to take care of underserved patients, and they have valuable trust-building, communication, cultural and language skills to be able to reach these populations effectively,” said Ortega, who also helped found Medical Organization for Latino Advancement (MOLA), a nonprofit devoted to supporting Latino physicians and students interested in medicine.

“It’s important that we facilitate the resources for medical schools, residency programs and faculty to create inclusive learning environments so that learners can thrive and become clinicians who provide excellent care to the populations that they want to serve.”

Ortega’s experience at Pritzker mirrored that approach. With the support of the school, she developed a medical Spanish course for students.

“From Day One, I was treated as a colleague by even the most senior physicians and faculty,” said Ortega, whose current research focuses on language proficiency assessment and how physicians can deliver language-appropriate care. “That type of environment is very nourishing, and it made medical education leadership feel natural to me.”

Last fall, Pritzker launched a newly revised framework known as the Pritzker Curriculum that prioritizes health equity education as a longitudinal thread throughout a student’s first three years. The curriculum includes a dedicated first-year equity course plus foundational courses and clerkships that incorporate patient advocacy and healthcare disparities discussions.

Applying these concepts on a wider scale would have an undeniably positive impact on the future of street medicine and the health of marginalized populations, Eisen said.

“This is very interesting, complex and meaningful work,” Eisen said. “To the extent that we can develop a workforce that’s dedicated to the needs of populations that are socioeconomically struggling or have other social determinant challenges, that really allows us to create more opportunity for care and recovery.”