Developing therapeutics for rare diseases is an uphill battle, Samuel Volchenboum, MD, PhD, MS, knows.

Researchers may struggle to obtain funding to study diseases that affect a small segment of the population — such as neuroblastoma, a pediatric cancer diagnosed in about 800 children each year in the United States. And rare diseases often lack enough standardized patient data to identify trends and biomarkers, evaluate treatments and stratify risk.

“Even the busiest hospitals will have only a few cases of any particular kind of pediatric cancer,” said Volchenboum, Professor of Pediatrics and Associate Chief Research Informatics Officer for the Biological Sciences Division (BSD) at the University of Chicago. “To make any headway, the community really has to come together and share clinical trials and data.”

This story appeared in Medicine on the Midway magazine. Read the Spring 2024 issue here.

With the help of advanced computational tools and partnerships, Volchenboum is leading a collaborative charge to collect and analyze pediatric cancer data from across the world.

As principal investigator of the fittingly named Data for the Common Good (D4CG), a group headquartered in the Department of Pediatrics at UChicago, Volchenboum facilitates sharing of health data from a wide range of institutions, groups and countries.

His goal is twofold: to support research breakthroughs and also to compile massive, highly detailed data troves that can do everything from helping tackle other rare diseases to aiding patients with more routine problems, like potential complications from being in the ICU.

“The work we do supports the entire spectrum of health research — from facilitating better ways to analyze genomic data to helping discern which patients are at risk for developing sepsis in hospital,” he said. “By harnessing the power of high-quality big data, analytics and new technologies, we can revolutionize how we treat millions of patients.”

The pursuit began decades ago. A lifetime of dual interests in computing and medicine led Volchenboum to consider throughout his MD and PhD studies how to become a “doctor who did computer science, rather than a computer scientist who dabbled in healthcare.”

His passions grew during a pediatric hematology/oncology fellowship at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Boston Children’s Hospital, and while pursuing a fellowship in informatics and a master’s degree in biomedical informatics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Today, the concept of biomedical informatics — which Volchenboum describes as “leveraging data, information and knowledge to improve human health” — supplies the foundation for his complex mission.

Data-driven discoveries help cancer treatments evolve

Pooling data resources to fuel breakthroughs isn’t new. In the 1960s and 1970s, hospitals all over the world treating pediatric cancers coalesced into cooperative groups to learn more about these deadly diseases and to collaborate on clinical trials.

“Pediatric oncologists could use the same treatment protocols in a consistent way and learn from every patient by bringing all the data together,” Volchenboum said. Over time, he noted, “many pediatric cancers that once were a death sentence are now cured 80 percent, and sometimes 90 percent, of the time.”

But they could do better, he thought, especially with more computing power.

Volchenboum joined the University of Chicago faculty in 2007, where he started a research group that would become D4CG. Initially targeting neuroblastoma, the team broadened their focus in 2019 to include other pediatric cancers.

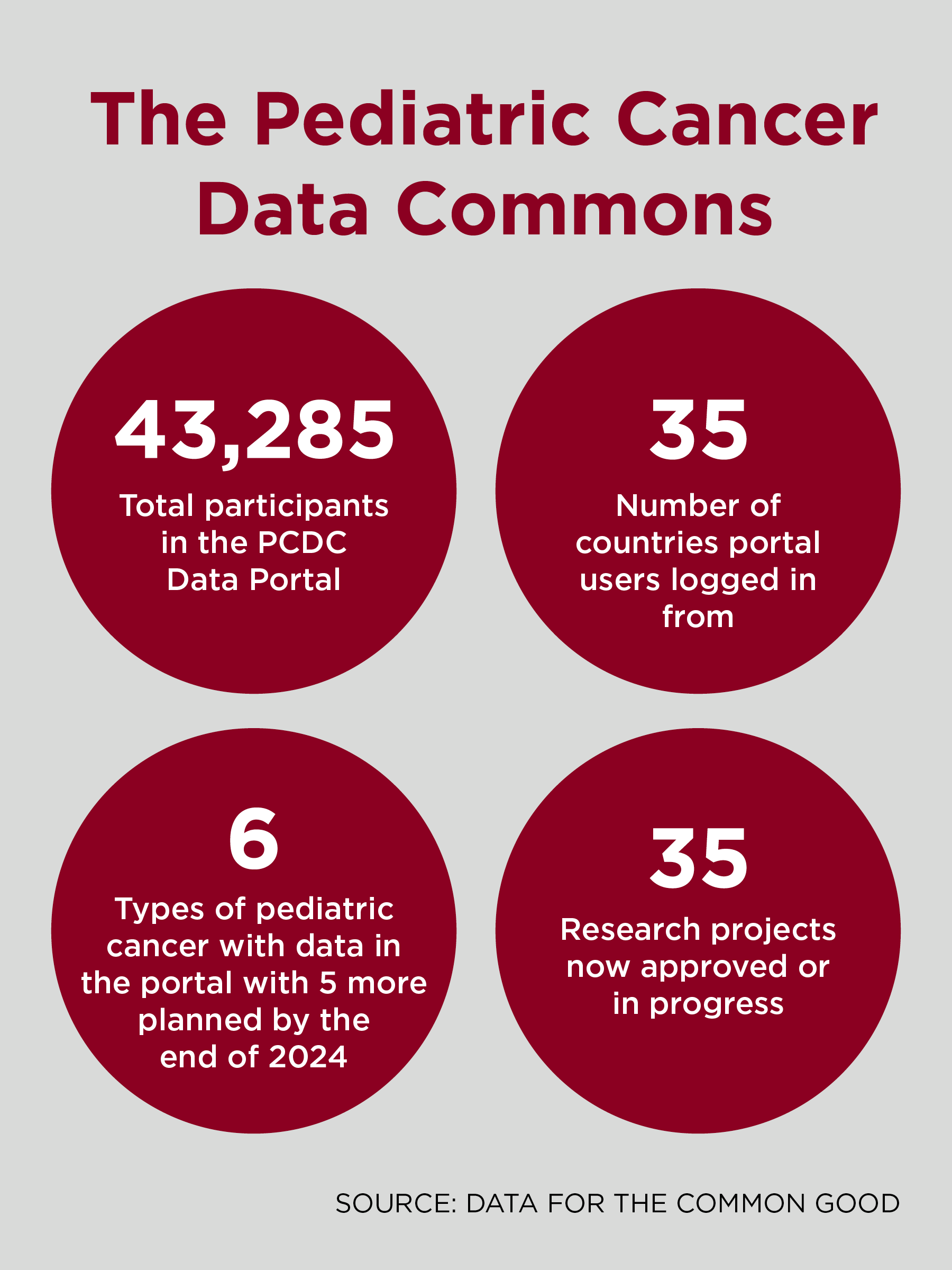

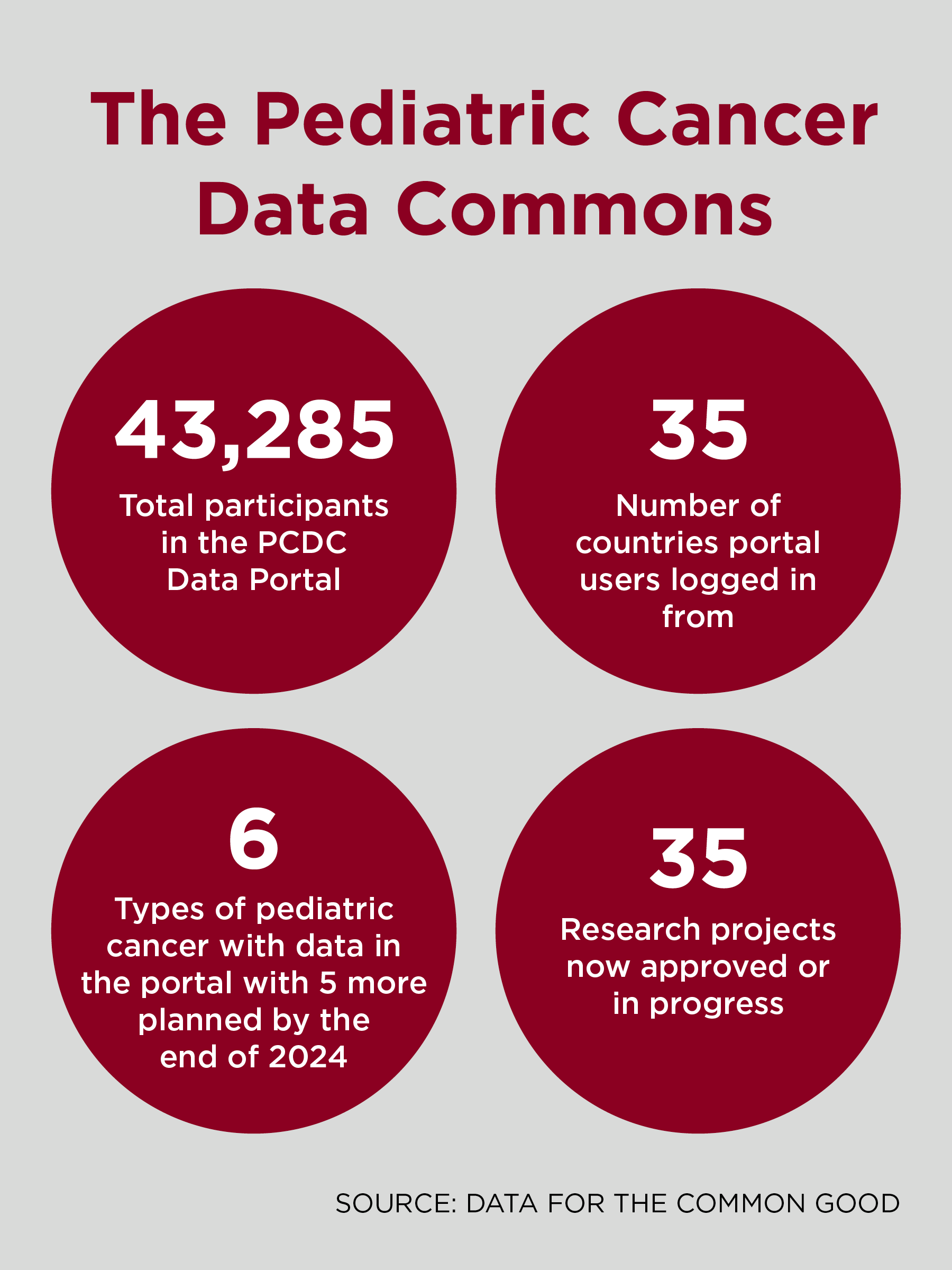

This led to the creation of D4CG’s flagship project, the Pediatric Cancer Data Commons (PCDC), which collects cancer data from around the world. The PCDC Data Portal, launched in 2021, makes the data available in a single platform for researchers.

“Imagine the power of taking data collected all over the world on these rare pediatric cancers over the past 30 years and harmonizing it all into a unified standard for researchers,” Volchenboum said. “We have over 43,000 kids’ data in the Commons, and we expect this number to grow considerably.”

Patterns and trends found in the data can inform progress. “Until recently, there weren’t many new drugs to treat pediatric cancers, but the way we use the drugs has changed dramatically,” Volchenboum said. “The ability to stratify patients based on genetic testing has also changed, allowing patients to receive the most appropriate treatment for their cancer. Further, new sensitive approaches to detecting residual tumor cells have made disease surveillance during and after treatment much more effective.”

In March, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy named the PCDC as one of five Champions of Open Science. Selected from a nationwide pool, the effort was cited in a statement from the White House for its mission “to push the boundaries of research and improve health” and its potential to aid the Cancer Moonshot.

Partnerships work to grow, unite cancer data collection

Not only does D4CG bring data together through international consortia, members also work carefully to standardize the information — a critical step for accurate, actionable analysis.

“Groups may collect data differently for features like biological sex or race and ethnicity, making it difficult to combine and aggregate data sets,” Volchenboum said. “Extrapolate that to much more complicated concepts like tumor stage or adverse events from chemotherapy, and it can be nearly impossible to bring these data sets together in a meaningful way.”

By addressing this issue, the PCDC has enabled substantial advancements in the ways children with cancer are treated, including:

- Better treatment approaches in pediatric non-rhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcomas

- Molecular testing in rhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcomas to improve risk stratification and outcomes

- Improved surgical management of paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma

- Proof that clinical trial participation leads to better outcomes for children with intermediate- or high-risk neuroblastoma

With growing interest from non-pediatric cancer groups in building similar platforms, Volchenboum’s group last year rebranded as D4CG to reflect a wider mission — and to tackle other diseases, particularly rare ones and rarer subtypes of common diseases.

Recently, D4CG has spearheaded work in monogenic diabetes and monogenic epilepsies, with seed funding from the Gray Foundation and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative DAF, an advised fund of Silicon Valley Community Foundation, respectively.

In addition to his international work, Volchenboum is deeply involved in bioinformatics efforts in Chicago. For six years, he ran the Center for Research Informatics at the University, providing support for the BSD as well as private industry — including high-performance computing, applications development and access to HIPAA-compliant storage.

He’s also the informatics core leader for the Institute for Translational Medicine (ITM), a partnership between UChicago and Rush in collaboration with Advocate Aurora Health, the Illinois Institute of Technology, Loyola University Chicago and Endeavor Health.

The institute, founded in 2007, is among about 60 sites in a nationwide network supported by the National Institutes of Health. It is currently leading a multidisciplinary consortium using D4CG’s expertise to build the Sociome Data Commons, a research platform for large-scale data analysis, including publicly available geocoded data sets about such nonclinical aspects affecting public health as social and economic factors.

New ideas, academic programs ahead

Volchenboum credits the University for supporting bold, cross-organizational collaboration, as well as guidance from faculty in public policy, computer science and precision health.

“Within the University community, there are very few constraints to trying a new approach,” he said. “Given the audacity of trying to create a worldwide resource for data sharing, one would expect pushback. On the contrary, there has been universal support for this important work, and I think this is a unique feature of the University of Chicago.”

Volchenboum, who also serves as Associate Dean of Master’s Education for the BSD, recognizes that the future of bioinformatics depends on new blood and ideas.

In 2023, the BSD and the University of Chicago Booth School of Business announced a new joint master of science in biomedical sciences and master of business administration program to pair foundational biomedicine training with leadership and management skills.

And this summer, Volchenboum will launch the Center for Data Democratization, a centralized resource for researchers worldwide. By convening interdisciplinary experts, the center will accelerate the understanding of fundamental questions in health and disease, build novel analytic tools and foster cohorts of clinical informaticians committed to scholarly investigation.

“A collaborative, standards-focused approach to collecting and using data has the potential to accelerate research in so many areas,” Volchenboum said. “Our ultimate vision is that access to high-quality data should never be a barrier to improving human health.”